ANTHROPOLOGICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ANCIENT NEAR EASTAnthropology 3328-1 (15271)/6328-1 (15272)

|

|

..

COURSE OUTLINE

|

| Instructor: | Dr. Ewa Wasilewska |

| Office hours: | By appointment only; please call the Department of Anthropology (581-6251) and leave your name, phone number, and class number. Email: Mruczek@AOL.com |

| Time: | Each Wednesday at 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. |

| Location: | CAMPUS - ST 205 |

| Important dates: | September 3, 2008 - last day to drop classes

September 8, 2008 - last day to register, to elect CR/NC option or to audit classes October 24, 2008 - last day to withdraw from term length classes |

Required Texts:

Optional and/or Recommended and/or Future Readings |

Mieroop, Marc Van De: A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000-323 B.C. Blackwell Publishing. 2007. (Mostly for historical background to avoid confusion since the compilation/collection of different texts is used throughout the semester.) Additional required texts are listed under specific topics. They are available at Marriott Library through the electronic reserve. The articles, chapters, etc., that, for different reasons, could not be placed on the electronic reserve are available as hard copies at the Reserve Desk. Most of these articles, chapters, etc., are not only short but also very interesting so DON’T PANIC! They are included at the end of each meeting. These readings ARE

|

| Subject: | This course is designed as an analytical survey of major events and discoveries in the Near East through studying archaeological evidence and available textual sources. While the focus of this course is on Mesopotamia, Iran, Anatolia, and Syria-Palestine, other areas such as Egypt will be discussed whenever relevant to the understanding of the primary interest cultures. Chronologically, this course covers data from the Neolithic period of time (prehistory: from hunter-gatherers to agriculturalists and early sedentism), through early urbanization (e.g., Ubaid, Eridu and Uruk), rise of complex societies (e.g., Sumer, Elam, Jiroft, Akkad), rise and fall of empires (Assyria and Persia) until the beginning of the Hellenistic period (the 4th century B.C.). Variety of archaeological sites will be discussed with regard to their layouts, character, archaeological landscapes, excavated material remains, etc., as based on available archaeological, anthropological, ethnographic, art-historical and other data. |

| Requirements: | Though this is a lecture format course, discussions of selected theoretical topics will be encouraged and facilitated. Students will be responsible for leading these discussions after reading the assigned material. In addition to regular in-class exams each student will have to prepare material for the discussion of selected theoretical issues (see above) and a site report to be turned in at the end of the semester. Although students are encouraged to do their own research and select any site in the Near East that dates between the Neolothic and Hellenistic Period, the instructor is available for an "emergency" assistance. The following information will be required to be included and discussed in the site report: |

..

..

WEEK # 1: August 27, 2008

Introduction:

Defining the region: the Near East, the Middle East, and Orient? What, where, who, how?

Defining the discipline: archaeology as a part of humanities or social and behavioral sciences? From robbers to scholars.

Defining subdisciplines of the Near Eastern archaeology (Egyptology, Assyriology, Hittitology, Biblical archaeology, classical archaeology, etc.): labels and reality.

|

Discussion: Archaeology as a modern discipline. One archaeology or many? All about science or ideology? Politics and purity in archaeology. Readings for Week # 1: Required: Mieroop, Marc Van De: “ Introductory Concerns.” In A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000-323 B.C. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford. 2nd edition. 2007. Pp. 1-10. For discussion and a short review of history of archaeology of the ancient Near East: Yahya, Adel H.: “Archaeology and Nationalism in the Holy Land.” In Susan Pollock and Reinhard Bernbeck eds., Archaeologies of the Middle East. Critical Perspectives. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford. 2005. Pp. 66-77. (Also for Week 16). Chazan, Michael: “Putting the Picture Together.” In World Prehistory and Archaeology. Pathways through Time. Pearson education, Inc., Boston. 2008. Pp.36-71. (Also for Week # 2). Movie: Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: For various archaeological discoveries of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries. A rare book with interesting stories.

|

WEEK # 2: September 3, 2008

The first of the “firsts”?:

The “Neolithic Revolution.” From hunter-gatherers to agriculturalists and early sedentism. Climate, populations, plants, and animals – all in transition?

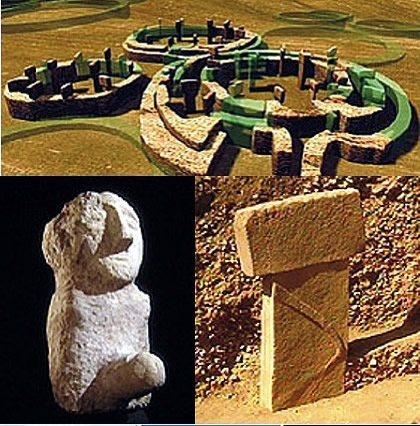

Neolithic settlements (selected case studies): Jarmo, Jericho, Ain Ghazal, Göbekli Tepe.

Çatal Hüyük: defining a site and its ideology.

Discussion: New approaches in archaeology. Binford vs Hodder: strict science vs reflexive method. Readings for Week # 2: Required: For a short overview of this time period see: For an excellent summary of major theories and transition to the Neolithic see: For interpretation of figural representations of the Neolithic Period see: Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: For an information about dating, C14, maps, and brief references to various sites see: For learning about ethnoarchaeology and its application to the Neolithic see: For Cauvin’s controversial ideas about the origin of agriculture see: For Çatal Hüyük see: For scientific reports about this site check this website. |

|

WEEK # 3: September 10, 2008

The Urban Revolution – figment or reality?:

Defining a city: transition from rural to urban life.

Emergence of social complexities with (e.g., Mesopotamia) or without (?e.g., Egypt) cities.

The Uruk phenomenon: the city of Inana and their “quest” for “power.”

Divine economy and profane writing (invention of cuneiform script).

|

Discussion: Ideology and IRS. Emergence of ceremonial centers, divine cities, and cities of the dead. Contrasting views from Mesopotamia and Egypt. Readings for Week # 3: Required: Mieroop, Marc Van De: “Part I City States. Section 2: Origins: the Uruk Phenomenon. Section 3: Competing City-States: The Early Dynastic Period.” In A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000-323 B.C. Blackwell Publishing. 2007. Pp. 17-62 (Also for weeks # 4-6, and 9). Roaf, Michael; “Toward Civilization (7000-4000 B.C.).” In Cultural Atlas. Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East. Andromeda Oxford Limited. 2002. Pp. 42-56 For origin and development of the cuneiform script see:

|

WEEK # 4: September 17, 2008

One civilization or too many? (Part 1):

Defining a civilization: methods and/or theory.

From the West to the East: the third millennium B.C. civilizational “boom” (Egypt, Sumer, Akkad, Elam, Jiroft, the Indus Valley).

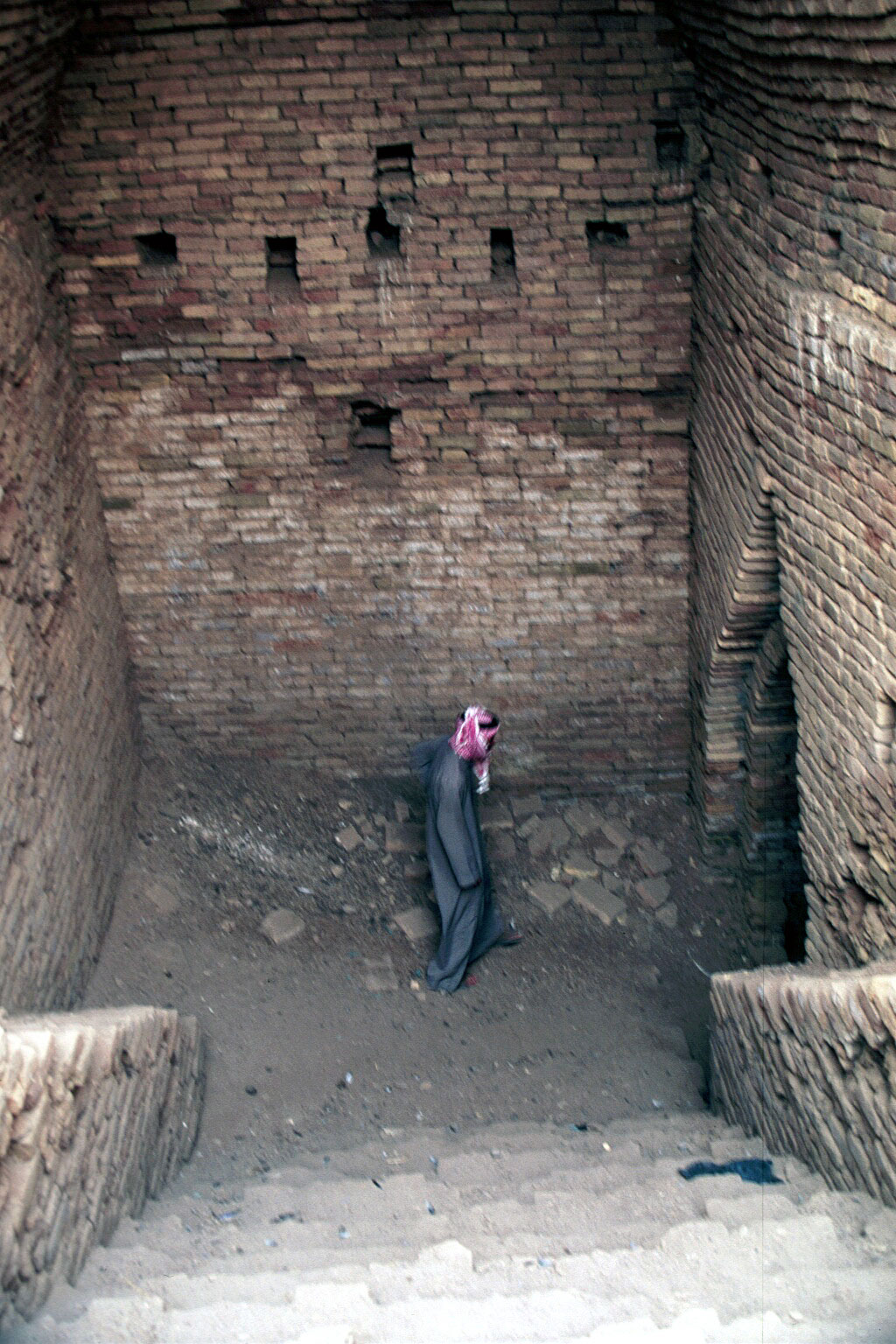

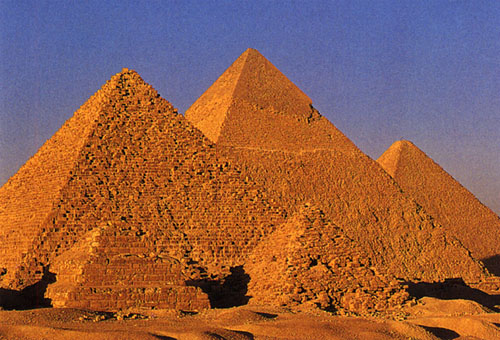

Monumental structures and their divine occupants: temples, ziggurats and pyramids.

Discussion: Archaeology of death: burial practices and their recognition in archaeological material (e.g., Ur, Giza). Readings for Week # 4, 5, 6: Required: Buren, Mary Van & Janet Richards: “Introduction: ideology, wealth, and the comparative study of ‘civilizations.’” In Buren, Mary Van & Janet Richards, eds. Order, Legitimacy, and Wealth in Ancient States. Part I: Order, Legitimacy, and Wealth in Ancient States. Cambridge University Press. 2000. Pp. 3-12. Baines, John & Norman Yoffee: “Order, legitimacy, and wealth: setting the terms.” In Buren, Mary Van & Janet Richards, eds. Order, Legitimacy, and Wealth in Ancient States. Part I: Order, Legitimacy, and Wealth in Ancient States. Cambridge University Press. 2000. Pp. 13-17. For introduction to the third millennium B.C. see: For introduction to the Egyptian and the Indus Valley civilizations see: For Jiroft civilization and its discovery see: For interpretation of the importance of the Royal Cemetery at Ur see: Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: Pearson, Mike Parker: “Learning From the Dead.” In The Archaeology of Death and Burial. Texas A&M University Press College Station. 2000. Pp.1-20. For Royal Cemetery at Ur see this very introductory site. Movies: |

|

WEEK # 5: September 24, 2008

One civilization or too many? (Part 2):

Defining a civilization: methods and/or theory.

From the West to the East: the third millennium B.C. civilizational “boom” (Egypt, Ebla, Sumer, Akkad, Elam, Jiroft, the Indus Valley).

Monumental structures and their divine occupants: temples, ziggurats and pyramids.

|

Discussion: Archaeology of death: burial practices and their recognition in archaeological material (e.g., Ur, Giza, Jiroft). Readings for Week # 4, 5, 6: see above.

|

WEEK # 6: October 1, 2008

EXAM !!!

WEEK # 7: October 8, 2008

Sacred vs profane:

Religion as a non-existing concept in polytheistic and henotheistic societies of the Near East in the third millennium B.C.

Ideological fundamentals: deities, divine rulers, creations, destructions, and maintenance. Thousands gods and goddesses and earthly subjects they ruled.

Discussion: Archaeology of religion: understanding ideology through material remains and ancient texts. Readings for Week # 7 & 8: Required: For information about archaeology of religion as a discipline see: Wasilewska, E.: “The Search for Impossible: the archaeology of religion of prehistoric societies as an anthropological discipline.” Journal of Prehistoric Religion, vol. VIII, 1994. Pp. 62-75. Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: For information about the “sacred” see: |  |

WEEK # 8: October 15, 2008

FALL BREAK!

WEEK # 9: October 22, 2008

Great vs Little Traditions:

Royal ideology: from theocracy to divine sponsored secularism.

Political centralization and decentralization at the end of the third millennium B.C.

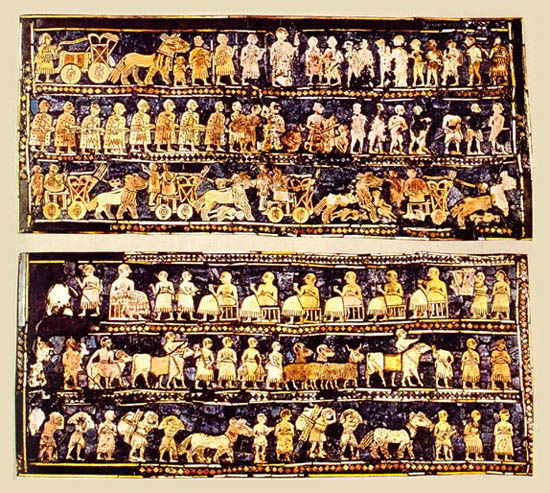

Art and architecture: the elite’s orders and people’s delivery.

|

Discussion: Art history or history through art? Archaeology of aesthetics or ideology? Cognitive archaeology. Readings for Week # 9: Required: Refresh your readings from Weeks # 4-6 on the situation in the ancient Near East during the Early Dynastic Period and continue with the rest of the third millennium B.C.: For discussion of “art” and ideology see: For introduction to art and architecture of the 3rd millennium B.C. see: Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: For learning about everyday life see: |

WEEK # 10: October 29, 2008

“Men in power” – a new social reality in the Near East:

Defining nomadism: who, where, when and how?

“Globalization” of the second millennium B.C.: the so-called Asian, Dravidian, Indo-European, Canaanite and African connections.

The Semitic Dominance: Babylon, Ebla, Aleppo, and Mari.

Discussion: Archaeology of gender. From new laws (e.g., Hammurabi’s laws, Middle Assyrian laws) to issues of gender and sexuality as represented in archaeological material. Readings for Week # 10: Required: For historical background of the first part of the second millennium B.C. see: For discussion of Syrian archaeology of the first part of the second millennium B.C. see: For discussion of gender and body perceptions see: Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: For discussion of issues of gender in archaeology see: Meskell, Lynn M.: “Chapter 2. Writing the Body in Archaeology.” In Alison E. Rautman ed., Reading the Body. Representations and Remains in the Archaeological Record. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2000. Pp. 13-21. For understanding sexuality in Mesopotamia see: |

|

WEEK # 11: November 5, 2008

Of horses, chariots, boats, and newcomers:

The Hyksos question: merchants and mercenaries.

The Hittite empire: architecture of defense, policy of offense, and freedom of speech for all (Yazilikaya).

The Battle of Qadesh: international conflict and solution.

The end of the 2nd millennium B.C.: the Kassites, Elamites and the Sea People.

|

Discussion: Archaeology of war and power. Setting foundations for the emergence of nationalism. Readings for Week # 11 & 12: Required: For basic information on the Hyksos see: For historical background of the second part of the second millennium B.C. see: For information regarding Hittite kingships, warfare and religion see: Bryce, Trevor: “6. The Warrior.” In Life and Society in the Hittite World. Oxford University Press. 2002. Pp. 98-118. Bryce, Trevor: “8. The Gods.” In Life and Society in the Hittite World. Oxford University Press. 2002. Pp. 134-162. Macqueen, J.G.: “Warfare and defense.” In The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor. Thames & Hudson. 2003. Pp. 53-73. Macqueen, J.G.: “Religion.” In The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor. Thames & Hudson. 2003. Pp. 109-136. Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: For more information about the Sea People see: For more information about Hittites and Anatolia see: Macqueen, J.G.: The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor. Thames & Hudson. 2003. For more information about Syrian powers of the second millennium B.C. see: |

WEEK # 12: November 12, 2008

EXAM !!!

WEEK # 13: November 19, 2008

Of one god, one sound, and plenty of “money” – Syria-Palestine of the 1st millennium B.C.:

Defining religion and monotheism: is there such a thing?

The rise of Yahweh and “survival” of Canaanite pluralism: inside the Old Testament and outside of material reality (“pagan” sanctuaries and practices). Old stories, new ideology.

At the crossroads of civilizations: trade and politics of wealth in Canaan. Invention of alphabetic scripts.

Who were the Phoenicians? The maritime supremacy and colonization.

Discussion: Underwater archaeology. Ancient populations, genetic markers, and modern reality. Readings for Week # 13: Required: For introduction to the Phoenicians and genetic markers see: Gore, Rick: “Who were the Phoenicians.” In National Geographic Monthly. Oct. 2004. For introduction to languages and scripts (especially alphabetic scripts) in Levant see: Rendsburg, Gary A.: “Semitic Languages (with Special Reference to the Levant).” In Suzanne Richard, ed., Near Eastern Archaeology. A Reader. Eisenbrauns. 2005. Pp. 71-73. For introduction to seafaring see: For introduction to religion see: Dever William G.: “Religion and Cult in the Levant: The Archaeological Data.” In Suzanne Richard, ed., Near Eastern Archaeology. A Reader. Eisenbrauns. 2005. Pp. 383-390. Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: Akkermans, Peter M. M. G. & Glenn M. Schwartz: “Iron Age Syria.” In The Archaeology of Syria. From Complex Hunter-Gatherers to Early Urban Societies (ca. 16,000-300 B.C.). Cambridge University Press. 2003. Pp. 360-397. For more information about underwater archaeology see: Manning, Sturt W. & Linda Hulin: “Maritime Commerce and Geographies of Mobility in the Late Bronze Age of the Eastern Mediterranean: Problematizations.” In Emma Blake and A. Bernard Knapp eds., The Archaeology of Mediterranean Prehistory. 2005. Pp. 270-302. “Shipwreck of lost 'Sea People' found.” In CNN news. By Environmental News Network staff. For introduction to genetics etc., see: |   |

WEEK # 14: November 26, 2008

Of imperial ideology and secular glory:

The shame of Egypt: decentralization of pharaonic power.

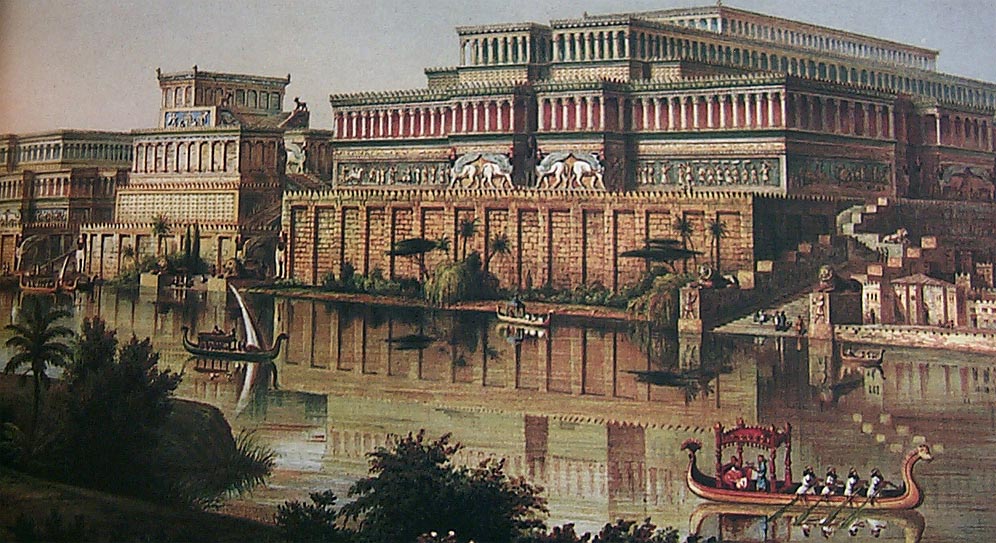

From a city-state to a territorial empire: the rise and fall of Assyria.

Art and architecture as visual ideology of Assyrian nationalism (e.g., palace programs).

|

Discussion: Social archaeology and creation of new identities. Archaeology of frontiers and collapse of "clay” economy. Readings for Week # 14: Required: For Assyrian palaces and their meaning see: For art and architecture see: Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: Strawn, Brent A. et al: “Neo-Assyrian and Syro-Palestinian Texts II.” In Mark W. Chavalas, ed. The Ancient Near East. Historical Sources in Translation. Blackwell Publishing. 2006. Pp. 331-381. For Urartian palace architecture see: For introduction to archaeology of frontiers see: |

WEEK # 15: December 3, 2008

Continuity, change, and fusion:

Tower of Babel and royal gardens of Babylon: a perfect city with imperfect rulers.

From nomads to rulers of the civilized world: the Medes and the Persians.

Under the leadership of Ahura Mazda: the free will of Zoroastrianism; justice for all and freedom for many; cosmopolitan art and architecture but … incompetent public relations “office.” The fall of the Persian Empire.

Discussion: Archaeologies of memory. Ancient past and modern politics: Iran as an Axis of Evil? Readings for Week # 15: For historical background see: For royal architecture of Babylon see: For Persian palace art and architecture see: Boucharlat, Rémy: “The Palace and the Royal Achaemenid City: Two Case Studies -- Pasargadae and Susa.” In Nielsen, Inge, ed., The Royal Palace Institution in the First Millennium B.C. Regional Development and Cultural Interchange between East and West. Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens. Vol. 4. 2001. Pp. 113-123. For art and architecture see: Optional and/or recommended and/or future readings: Arnold, Bill T. & Piotr Michalowski: “Achaemenid Period Historical Texts Concerning Mesopotamia.” In Mark W. Chavalas, ed. The Ancient Near East. Historical Sources in Translation. Blackwell Publishing. 2006. Pp. 407-430. For understanding of new post-Assyrian dynamics see: For understanding basics of archaeologies of memories see: |

|

WEEK # 16: December 10, 2008

Cultural heritage: its politics, economy, and academia.

|

Readings for Week # 16: Required: Postgate, Nicholas: “The First Civilizations in the Middle East.” In Archaeology: The Widening Debate. Barry Cunliffe, Wendy Davie, Colin Renfrew, eds. Oxford University Press. 2002. Pp. 383-410. Özdogan, Mehmet: “Ideology and Archaeology in Turkey.” In Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, politics and heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Lynn Meskell, ed. Routledge. New York. 1998. Pp. 111-123. Pollock, Susan: “Archaeology Goes to War at the Newsstand.” In Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives. Susan Pollock and Reinhard Bernbeck. Blackwell Publishing. Oxford. 2005. Pp. 78-96. Kaylan, Melik: “So much for the looted sites.” In Wall Street Journal. July 15, 2008. Cuno, James: Who owns antiquity? Princeton University Press. 2008. Alberge, Dalya: “Phaistos Disc declared as fake by scholars.” In The Times Online, July 12, 2008. |

WEEK # 17: December 17, 2008

EXAM !!!

Last day to turn in your papers.

IMPORTANT!!!

IMPORTANT!!!

ACADEMIC MISCONDUCT

Please familiarize yourself with the University of Utah CODE OF STUDENT RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES (“STUDENT CODE”) at www.admin.utah.edu/ppmanual//8/8-10.html

The following is an excerpt from this CODE explaining specific actions, which won’t be tolerated in this class.

“2. “Academic misconduct” includes, but is not limited to, cheating, misrepresenting one's work, inappropriately collaborating, plagiarism, and fabrication or falsification of information, as defined further below. It also includes facilitating academic misconduct by intentionally helping or attempting to help another to commit an act of academic misconduct.

a. “Cheating” involves the unauthorized possession or use of information, materials, notes, study aids, or other devices in any academic exercise, or the unauthorized communication with another person during such an exercise. Common examples of cheating include, but are not limited to, copying from another student's examination, submitting work for an in-class exam that has been prepared in advance, violating rules governing the administration of exams, having another person take an exam, altering one's work after the work has been returned and before resubmitting it, or violating any rules relating to academic conduct of a course or program.

b. Misrepresenting one's work includes, but is not limited to, representing material prepared by another as one's own work, or submitting the same work in more than one course without prior permission of both faculty members.

c. “Plagiarism” means the intentional unacknowledged use or incorporation of any other person's work in, or as a basis for, one's own work offered for academic consideration or credit or for public presentation. Plagiarism includes, but is not limited to, representing as one's own, without attribution, any other individual’s words, phrasing, ideas, sequence of ideas, information or any other mode or content of expression.

d. “Fabrication” or “falsification” includes reporting experiments or measurements or statistical analyses never performed; manipulating or altering data or other manifestations of research to achieve a desired result; falsifying or misrepresenting background information, credentials or other academically relevant information; or selective reporting, including the deliberate suppression of conflicting or unwanted data. It does not include honest error or honest differences in interpretations or judgments of data and/or results.”

The following sanctions will be imposed in this class for a student engaging in academic misconduct:

1. A failing grade for the specific assignment, paper, exam, etc., without possibility to re-write it, re-take it, etc. This academic misconduct will be reported to the Chairman of the Department of Anthropology.

2. The second offense will be sanctioned with a failing grade for the whole course. In such a case, the following rule of the University of Utah CODE OF STUDENT RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES is applicable and will be followed: “If the faculty member imposes the sanction of a failing grade for the course, the faculty member shall, within ten (10) business days of imposing the sanction, notify in writing, the chair of the student’s home department and the senior vice president for academic affairs or senior vice president for health sciences, as appropriate, of the academic misconduct and the circumstances which the faculty member believes support the imposition of a failing grade.”

3. For more information concerning sanctions for academic misconduct (additional sanctions might be imposed) and your rights and procedures to appeal these sanctions please refer to the aforementioned CODE.

If you need more information and/or explanations please don’t hesitate to contact the instructor.

| Download this document as PDFor Word file |